Cuphead: Gettin’ Got by Goopy LeGrand

It’s something to be said that I felt a more profound feeling of accomplishment when I finally defeated Goopy LeGrand than I did the day I graduated with a Master degree. One of these involved repeated and painful failures, regular practice, labored study and analysis, and a tremendous amount of work.

The other activity involved acquiring a Master’s degree.

Cuphead was developed and released by StudioMDHR Entertainment Inc. 29 September 2017 for Windows personal computers and Xbox One; it was later released in 2019 for the Nintendo Switch and in 2020 for Playstation 4. In 2022 the game received an official add-on known as The Delicious Last Course. I note for the historical record I have nothing to say about this add-on because, as of this writing, I haven’t even gotten past the first island of the original game. Cuphead is many wonderful things: a side-view, 2D scrolling, fantasy-action platformer and shooter, and it is also devastatingly challenging to the point of being sadistically cruel. When I told a coworker I was playing through it she told me, and this is an exact quote, “Oof, enjoy your rubber-hose Dark Souls.”

For clarification my coworker had a degree in animation and was making a reference to the visual aesthetic of Rubber-Hose animation which was popular during the 1920s. This unique visual style became extremely popular until the mid 1930s when the Disney Corporation began to achieve commercial and critical success with more photorealistic animation. It wasn’t until the 2010s before Rubber-Hose began to achieve a cultural re-emergence and Cuphead is often credited as the main actor for that resurgence.

As to why she referred to Cuphead as Dark Souls well(*adds penny to the reference cup*) the game is unforgiving, and death is a certainty rather than a possibility.

To wit.

I died a multitudinous number of times before I even got to the third stage of Goopy LeGrand’s fight. This is entirely because I didn’t recognise how important motion, and more importantly patience was to actually playing Cuphead. There is no difficulty setting in the game therefore players are given an even playing field, and the only true way to progress is to die over and over again while learning the in-game mechanics and studying the individual level designs.

Cover Art image provided by The Cover Project.

Goopy LeGrand is not the first level of Cuphead, that’s actually a run-and-gun level called Forest Follies that I want to write about in the future. Actually if I’m being honest I want to write about every level in Cuphead, but I haven’t figured out yet how to do that without it becoming boring and painfully repetitive. Stay tuned. Players chose to play as Cuphead or Mugman who are both in trouble for gambling their souls at The Devil’s casino. It’s not even a metaphor the opening cinematic (a gorgeously shot homage to animed films from the 60s) shows a book that tells how Cuphead and Mugman bet their souls and now owe the literal Devil his due. After losing a game of…(craps?(maybe?(I don’t gamble so names are lost on me))) The Devil informs the boys they can avoid damnation by collecting the errant souls that also owe the Devil. After a quick training session CupHead and MugMan set about finding these debtors. Cuphead is broken up into missions that are reached by exploring an overworld map similar to one in Super Mario Bros.3. Some missions are run-and-gun missions where players run through a platforming course while avoiding (and shooting) enemies to get to the end, some missions are effectively shoot ‘em ups where CupHead and MugMan control planes, and finally there are, for lack of a better word, Boss Fights.

Goopy LeGrand’s mission “Ruse of an Ooze” is one of the latter.

Boss Fights are structured so that Cuphead (or Mugman(or both if you can get a friend to join you in this entertaining and painful endeavor) is fighting a large enemy non-playable character(npc). While it’s usually one single opponent, some Boss Fights will have players pitted against two or three enemies, however fights like this are typically organized so that Cuphead will fight one boss after another in succession. Likewise Bosses are structured aesthetically according to the nature of the bosses themselves. To wit when fighting The Root Pack the fight will take place on a farm, when fighting Ribby and Croaks the fight will take place in the ballroom of a steam-boat, and finally when fighting Hilda Berg the fight will take place in the air above Inkwell Island.

Goopy LeGrand’s level is just a pocket of the forest, and while The Root Pack(three vegetables that are literally a potato, an onion, and a carrot(hence the name root(get it?))) is often portrayed as the first real Boss Fight, I’ve always considered Goopy to be the actual first boss. This is entirely subjective on my part and players can progress in any direction they want. But the fact that Goopy’s level is just a clearing in the woods, and the character himself is just a borderline rip-off of the Slimes from Dragon Quest, I feel comfortable arguing that he is in fact the true first boss of the game.

I want to clarify immediately concerning that last sentence, I don’t actually believe Goopy is a rip-off of Slimes.

It’s just…they’re both amorphous blobs, and they’re the exact same shade of blue.

I mean come on, how am I NOT supposed to make that connection?

Just saying.

Goopy’s fight, like all boss fights in Cuphead, is structured in multiple phases. Throughout Cuphead players will fight bosses and once they reach a specific damage point the boss will undergo a physical transformation or alter their attack patterns. Part of the fun (and agony) of Cuphead is that bosses don’t have health point bars meaning players have no idea when a boss will transform or shift strategies; there is no way to determine how far along in the fight I am unless I die. This creates what I can only describe as a sublime tension because once the fight begins I have to remain in fight and/or flow state until a victory is triggered and the battle ends.

Or if I die.

Which is far more likely.

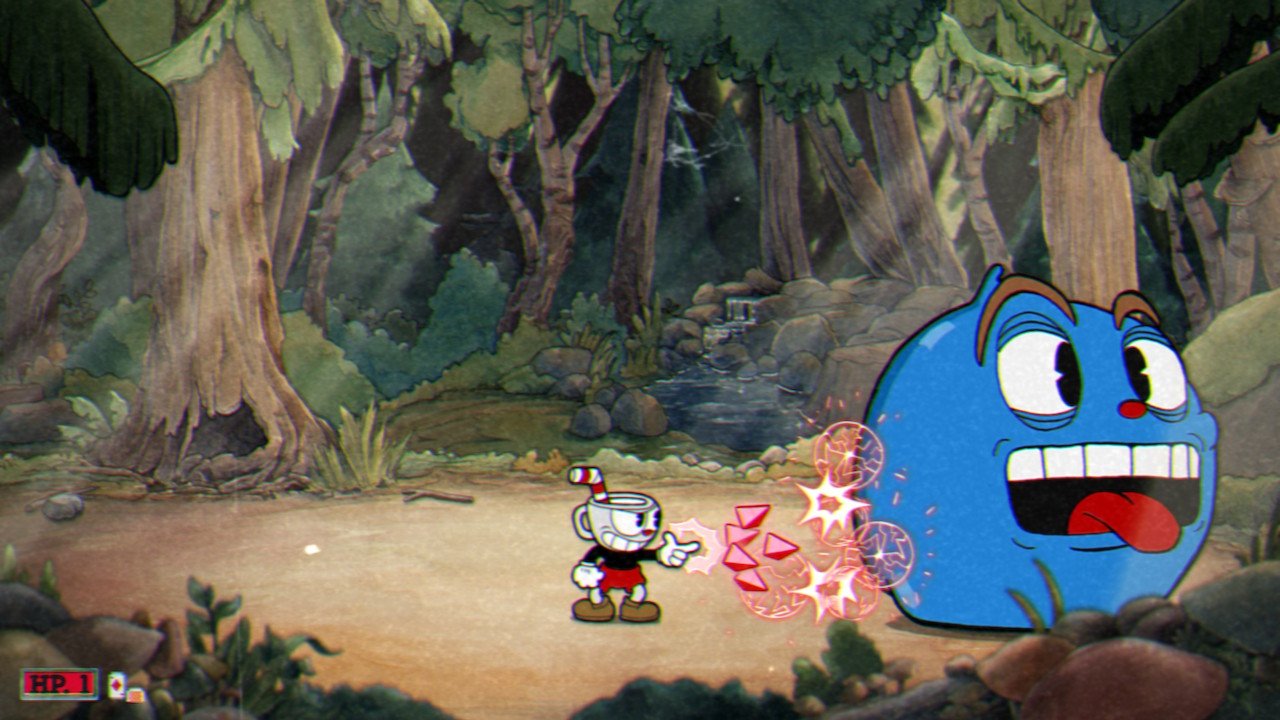

Goopy’s fight is broken up into three phases, and like every fight, it’s structured around continually moving Cuphead and firing. The fight begins with Goopy’s sprite, which is proportional to Cuphead and Mugman’s sprite in terms of size. Goopy will begin (say that five times fast(I dare you)) making large bounds across the screen in the direction of Cuphead. These are, honestly, pretty easy to avoid. Goopy’s body is such that he doesn’t take up a large amount of space and I can run, jump, or dodge the attacks with no amount of difficulty. There is some challenge as Goopy will occasionally stop, swell up in size, rear back, and manifest into a large boxing glove that tries to hit Cuphead. Again this is rather easy to avoid.

The second stage of the fight is when the challenge increases because, in a quick animation Goopy will flip a pill into his mouth (he has arms that appear when he wants them to) and he will immediately swell up into a gargantuan wad that takes up easily a quarter of the screen. At this point his jumping will resume and now the player has a smaller window of space to avoid the colossal tub that’s attempting to collide with him. This part of the fight was typically, during my first few playthroughs, the area where I died the most. It’s not difficult to anticipate where Goopy will fall, it’s just the sheer size of the gluttonous ball would always swallow up whatever space I had to move forward. Likewise Goopy will regularly stop, manifest an arm (this time decorated with a red boxing glove), and try to punch cuphead.

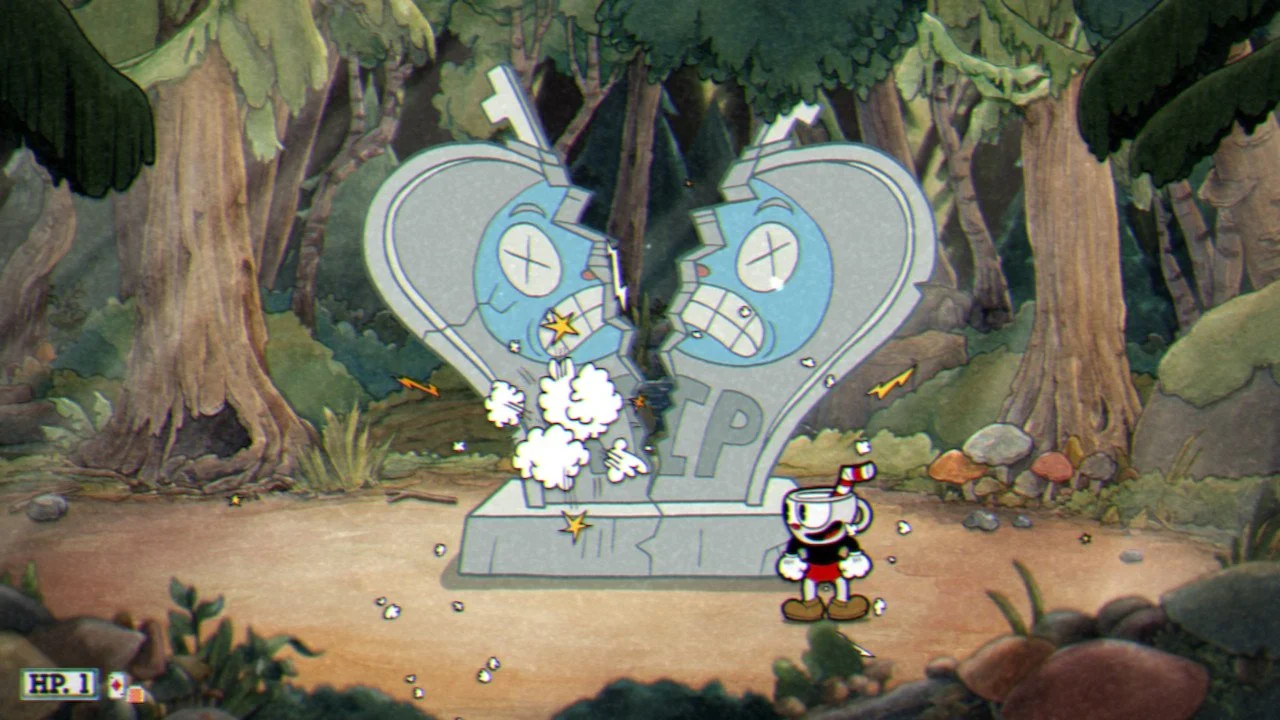

The last phase of the battle begins when Goopy apparently dies. Typical to cartoons of the past his eyes cross, spirals and stars appear above his head, his tongue hangs out, and he wobbles back and forth. Players have a second to appreciate a supposed victory before Goopy explodes into a cloud until his literal tombstone appears and begins shifting left and right across the screen, stopping frequently to slam down upon Cuphead. This last phase of the fight continues to emphasize the importance of moving Cuphead and situating himself in just the right spots. Most importantly is learning how to dodge attacks. Goopy’s Tombstone moves quickly, and just like the previous phases, players will have to study Goopy’s Tombstone's movements to determine when they will need to dodge its attack. And all of this is punctuated by the fact that the only vulnerable point on the Tombstone is Goopy’s face, which is a smaller target.

I feel confident in saying that at least 90%of my playthroughs that included getting to this final phase ended in being crushed.

I don’t have any hard data to support this, and now I need to make a brief aside.

At this point in the game I really wish I had possessed enough foresight to keep track of my deaths because I know it would make a wonderful spreadsheet, and because I’d honestly like to see the data of loss vs. victory in the game so far. I know for a fact that I have played Goopy’s boss fight at least 30 times, and out of those 30 times conservatively I won at least four rounds. These numbers are, I need to emphasize, speculative at best; I have no idea how many times I actually fought Goopy LeGrand before I finally won.

Before my reader says anything, I know.

I have failed science and ludology because I was lazy and didn’t anticipate how important that data would be. My methodology has been flawed.

This shame shall follow me into whatever afterlife may exist, and I will be punished for my failure most likely by being forced to play Battle Toads until the end of eternity.

If I may muster some defense, I would argue the specific number of failures is not as important as the fact that I recall the failure of losing to Goopy far more than actually beating him. This says a lot about the design of Cuphead as a videogame, and, I would argue, also reveals some really interesting narrative and rhetorical structures.

As I noted earlier, Goopy’s level is designed in stages to provide challenges to the players to test their familiarity with the in-game controls: running, shooting, dashing, and jumping. Fighting Goopy is about continually moving left and right to avoid his jumps and punches, and players (who pay attention) will over the course of the fight begin to recognise the pattern. I want to make it clear I didn’t pay attention at first and that’s one of the reasons I died so frequently. Even after I started paying attention though I still found myself dying because I was not reacting in time to the in-game clues. Pattern recognition is at the heart of Cuphead’s design philosophy and every level of the game relies on it.

For this reason alone I would argue Cuphead is as much a puzzle videogame as it is a shooter and platformer.

Puzzle videogames challenge players to recognise patterns in order to find solutions, and while puzzle elements tend to be incorporated into action-based videogames for the purposes of mini-games and/or sidequests, Cuphead’s design is fascinating because the puzzle is the game itself. Every Boss and every Run-and-Gun mission requires the player to interpret the data they receive and then find a solution before enemy npcs make contact. In the case of Goopy LeGrand the puzzle becomes about how to quickly locate and reach an ideal location. While this is admittedly the core experience of any platformer game, Cuphead pushes it so that players are continually solving puzzles while trying to shoot.

And, this is important, failure is inevitable.

And story-wise this makes absolute sense.

Looking back at what my co-worker said about Cuphead, she was entirely right to refer to it as (*another penny in the reference cup*) “Rubber-hose” Dark Souls. The joke is that players can expect to die…a lot, but looking at all of these failures from a rhetorical perspective this makes absolute sense. Dark Souls is a videogame about failure, specifically how human beings have failed to unify against the forces of darkness, and how the structures of power have failed to use their gifts to make the world a better place. From the beginning of the game the story of Cuphead is about failure: Cuphead and Mugman failed to listen to their grandfather who advised them not to go to the Devil’s casino. Admittedly it was mostly Cuphead, but they still both made decisions that had consequences. Cuphead fails at a dice roll, and this prompts The Devil to call to collect. The list of debtors that Cuphead and Mugman receive are also people who have failed and now also owe the Devil their eternal soul.

If it isn’t clear at this point, every narrative facet of Cuphead is about exploring failure.

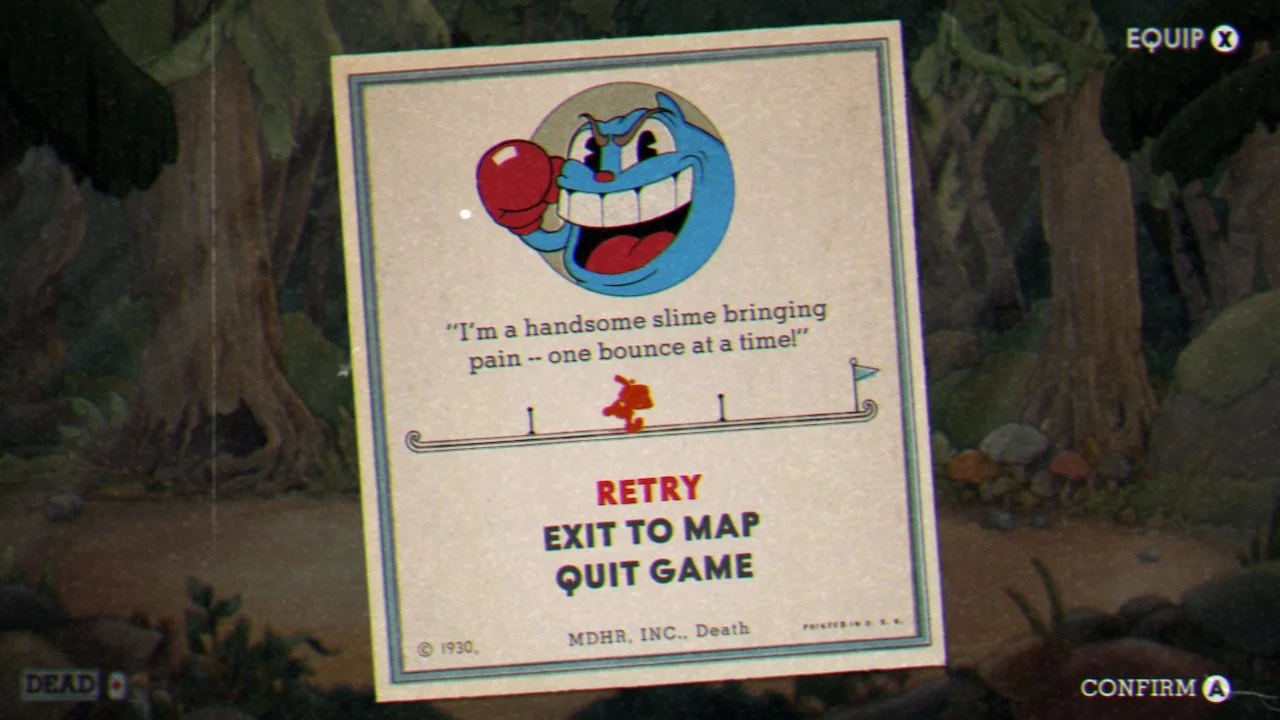

Failure in videogames ultimately amounts to losing; it’s the familiar “Game Over” screen that greets players when Mario hits a Koopa Troopa, when Link dies in Ocarina of Time and has no fairies in a bottle, or when Cuphead is smashed by Goopy’s tombstone and floats up and away like cigarette smoke. A while back I wrote a review of the book The Art of Failure: An Essay on the Pain of Playing Video Games by Jesper Juul, and one quote from the book provides a wonderful context for why Goopy’s fight, and all of Cuphead works as much as it does. Juul writes:

It is the threat of failure that gives us something to do in the first place. It is painful for humans to feel incompetent or lacking, but games hurt us and then induce an urgency to repair our self image. Much of the positive effect of failure comes from the fact that we can learn to escape from it, feeling more competent than we did before. This connects games to the general fact that it is enjoyable to learn something, but it also shows games as different from regular learning: we are not necessarily disappointed if we find it easy to learn to drive a car, but we are disappointed if a game is too easy. This means that failure is integral to the enjoyment of game playing in a way that is not integral to the enjoyment of learning in general. Games are a perspective on failure, and learning as enjoyment or satisfaction. (45)

The narrative of Cuphead is about overcoming personal failure, and structurally the game is a series of puzzle/platforms that challenge players to recognize patterns and then find a solution. Narratively speaking players will fail and every death is only reinforcing the story that Cuphead and Mugman are paying for making their original mistake. Likewise from a structural perspective every time the player dies it’s because they did not pay enough attention to the designs that make the game as infuriatingly difficult and fun as it is. Goopy LeGrand is the first real demonstration and manifestation of all of this failure.

And, I’ll say it again, he killed me…a lot, like, a LOT dude.

I died, I failed to beat Goopy over and over again, and each loss was painful and frustrating, and I frequently rage-quitted this game and switched over to Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild to cool down and grab some more Korok seeds.

Eventually however I couldn’t let it go. I watched YouTube Playthroughs, I read as many guides and reddit posts as I could, and then I just played the game over and over again to the point that I would laugh when I died. Everytime Goopy crushed me I would groan, laugh, raise my middle finger at the screen, call Goopy some names that would make a Rugby player blush, and hit the retry button again. Eventually I solved the puzzle and managed to beat Goopy LeGrand, relishing in my victory.

At least I did, until I started fighting Hilda Berg and as of this writing I still haven’t beaten her.

There’s solace in the fact that my endless failures to beat Goopy LeGrand were lessons I’ve internalized, and I know now that even after I defeat Hilda Berg there’s still more Boss-Fights awaiting me that will assuredly result in even more failures. Maybe this time I’ll actually remember to make up those spreadsheets to keep track of said failures, and that way I'll at least have a specific number to point to when I need to explain why it’s taken so long to get off of the first Inkwell Island.

Joshua “Jammer” Smith

10.24.2025

Like what you’re reading? Buy me a coffee & support my Patreon. Please and thank you.