Legend of Zelda: Link's Awakening & the Gameboy Printer

There’s a mouse with a camera that appears out of nowhere and takes photos of Link.

At first glance that sentence feels like it was randomly generated through an AI text program or my brain after I told myself I would only have one glass of Jägermeister (it was only one…glass), but believe it or not it’s actually based in reality. And on the note of reality I’m going to have to check mine because this essay is actually going to be more about a hardware addition to a videogame console than a specific videogame itself. It is me however, so I guarantee you by the end of this peculiar essay I’ll have something to say about the rhetorical significance of an npc dedicated to promoting the use of a hardware addition to a handheld console.

On a related note, I’m genuinely surprised Norman Caruso, a.k.a. the Videogame Historian has never done a video about this add-on given the fact that he has a whole playlist on his YouTube channel entirely dedicated to videogame hardware. Then again that dude’s probably busy being awesome, plus he’s in a podcast with his wife these days so his research window is smaller.

Plus he’s made a video already about Legend of Zelda: Link’s Awakening so I’m gonna cut the man some slack.

The Gameboy color was an 8-bit hand-held console released by Nintendo in North America in November of 1998. I remember the release with a mixture of obsession and tragedy; I wanted a Gameboy the way a man lost in the desert wants water. While my parents’ Super Nintendo Entertainment System (SNES) had been a wonderful foundation for my lifelong fondness for electronic interactive media, just about every boy my age who attended the private school I went to had a Gameboy. I can recall the pangs of furious envy that would consume me as I watched one of the other boys playing Super Mario Land or Wario Land oblivious to the fact that I was watching them in a pre-Andy Serkis manifestation of Gollum from The Lord of the Rings. As the Gameboy Color began manifesting into every third commercial break between cartoons, and being pasted into the glossy advertisements of magazines I’d read at the grocery store I realized that life would have absolutely no meaning or relevance if I didn’t own one.

Somehow I communicated all this to my parents (without being a total snot about it (I hope))because for my birthday they took me to the local WallMart and bought me one.

They also said I could pick any one game of my choice.

The choice came down between Wario Land 3 and Legend of Zelda: Link’s Awakening.

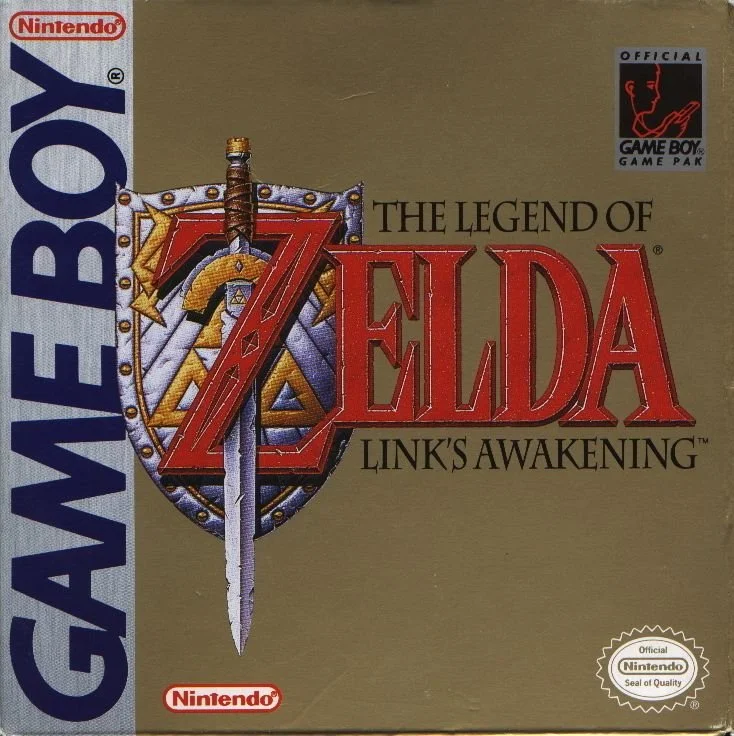

Now, obviously, given the title my reader already knows which one I picked, but I do want to comment that if my desperation for the majesty of the handheld Gameboy Color could be described as philosophical hunger, then I cannot express enough in words the way my soul was spinning with a fervent mania for Link’s Awakening. Though it had already been released for the Gameboy, Nintendo had re-released the game (under the title Link’s Awakening DX) which added color and additional content (specifically an entire dungeon centered around color). I had caught glimpses of Link swiping his blade at a chain chomp and jumping over moblins, and I had, at that time, spent most of my life playing Legend of Zelda: A Link to the Past. I didn’t even hesitate. The 2.5x12.5x12.5 cm cardboard box decorated with a sword, a shield, and a font style that criminally is not available in most word processors, stared back at me through the glass. I pressed my finger against the cool surface and went home with a new adventure in Hyrule in my lap.

Legend of Zelda: Link’s Awakening (both the original and DX versions) tell the story of Link, the classic hero of the series, who’s sailing on the ocean following the conclusion of the previous game A Link to the Past. An opening cutscene plays that shows Link caught in a storm and then washing upon a beach where a young woman named Marin discovers him and takes him to her home to recuperate. Once he wakes up Link returns to the beach to reclaim his sword and once he does, an Owl informs Link that he is on Koholint Island and the only way to ever make it home is to wake the Wind-Fish, a mystical being who is sleeping in a giant spotted egg on the central mountain of the island. From there Link must find eight magical musical instruments (say that eight times fast(I dare you)) held in eight dungeons, all while steadily learning more about Koholint island and the mystery of its origins.

There’s also a really fun trading side-quest that literally established the precedent in later Legend of Zelda games but today, I’m writing about the mouse with a camera.

After completing the first dungeon and securing the Full Moon Cello Link will return to Kohilint Village where, as he learns from the two boys playing catch by the library (instead of reading books) a gang of Moblins has appeared and taken Madam Meowmeow’s pet Chain chomp. Link will need to head north, and using the Roc’s feather he acquired in the first castle he will jump into a new region.

Along the way, Link will pass by a house with a blue roof and a camera on top.

Stepping inside there is a purple mouse, who’s name is literally Mouse, who’s holding a camera and just waiting. Now please remember that when I first played Link’s Awakening it was the late 90s, I was around 9-10 years old, and I was socially awkward little boy who spent an inordinate amount of time alone reading Calvin and Hobbes books, watching Swat Kats on T.V., and playing videogames. I wasn’t taken aback by the fact that there was a talking mouse holding a camera. But when I talked to him and he told me he wanted to take my photograph it was just such a dramatic break from the narrative flow that I stared at the screen for a few moments before I responded.

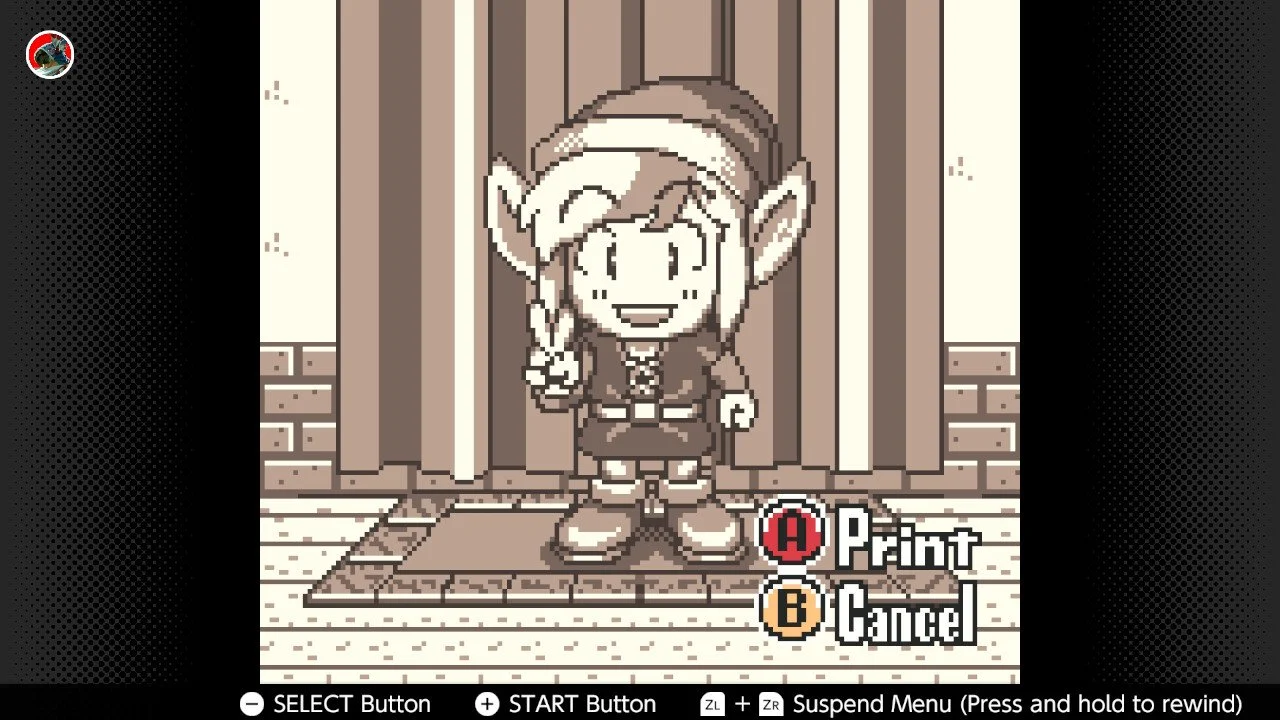

It’s been at least two decades since my first playthrough so I honestly can’t remember whether or not I said yes, but what’s important is if the player says no Mouse will literally push Link up against the curtain along the back of the wall and snap a photo. If the player picks this route the photo will show Link collapsed on the floor, his eyes a series of spirals looking hazard. If I say yes, the photo will be Link smiling and flashing a peace-symbol.

This is the first interaction with Mouse, and there are 11 more.

Triggering Mouse to arrive and snap a photo of Link will depend on certain key plot points in the game, how far the player has progressed in the narrative, and sometimes it’s simply walking into the right physical location and triggering him to spawn. As a character Mouse has no real personality besides the fact he loves to take photos (so…he's a photographer I suppose) and almost all of the interactions have some humorous bent to them.

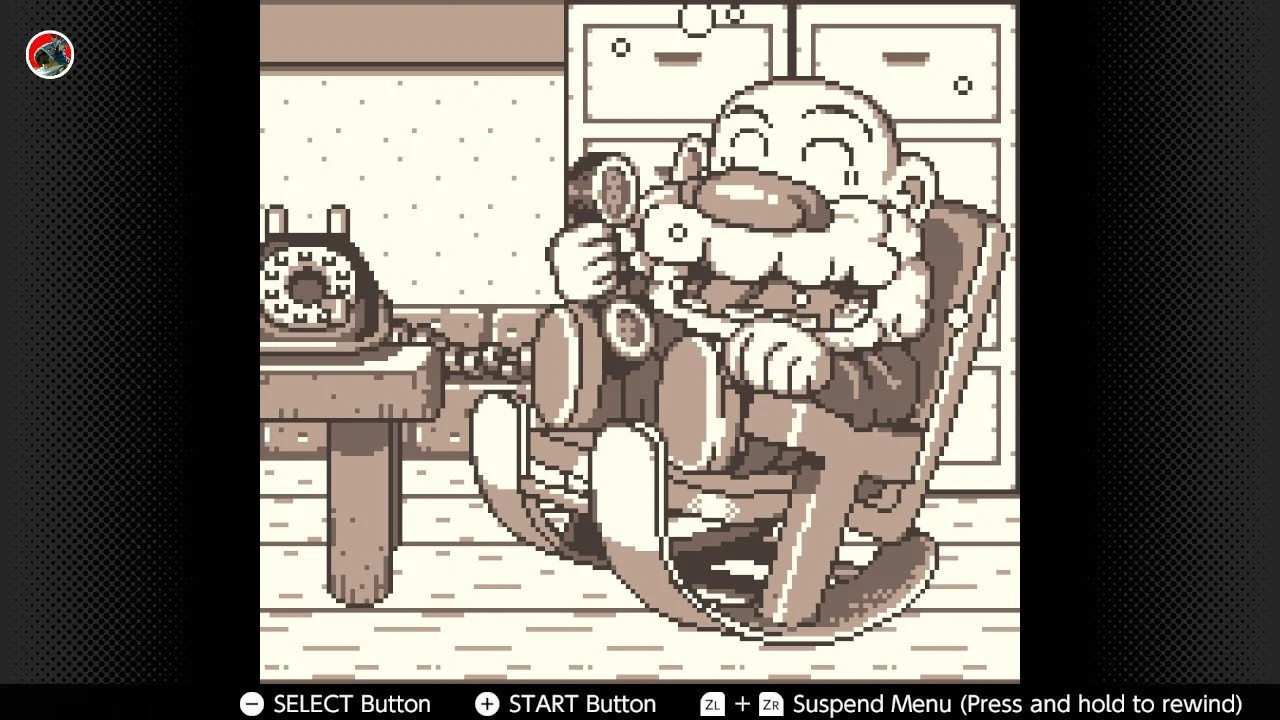

For example halfway through the game Link will ask Marin to accompany him to wake up a sleeping Walrus and as he leads her across the map there are two possibilities for photographs. One of them involves Link jumping down a well with Marin landing on top of him, and the second involves Marin and Link taking a photo in front of the Rooster statue in the center of town and being interrupted by Marin’s father Tarin (who’s definitely not Mario by the way(but he also definitely is(also at one point he gets turned into a raccoon))). Another example includes Mouse swimming underneath a fisherman’s boat (still not sure why he wasn’t just on the boat but, whatever, you do you man) and being caught before then taking a photo of Link and this Fisherman getting washed into the water while trying to catch a fish. In one of his llater appearances Mouse will meet Link on a rope bridge in the mountains and while trying to set up a beautiful shot, he’ll trip and fall off triggering the photo of Link looking down in horror at the fall, Mouse’s tail and padded foot appearing in the lower portion of the photograph.

These moments are funny in and of themselves, and discovering them was one of the reasons why Link’s Awakening left such a deep intellectual impression on me as a young man. The game was a strange mixture of reality bending, absurd humor, typical action-adventure content, and just visually distinct from any game I had played. Accidentally stumbling across this non-playable character (npc) who existed simply to take photos gave me more reason to explore Kohilint Island and whenever I would trigger a scene with Mouse I would log it in my memory banks to visit his house in the mountains and see the actual photo itself.

Looking at these photographs gave me an impression of time spent within the world of this videogame, and because I was playing at a time that was pre-smartphone there was a desire to physically hold these photographs.

Which is exactly where the hardware portion of this essay becomes relevant.

The Gameboy Printer (or Pocket Printer as it was called in Japan) was a small thermal printer that could attach to the Gameboy Color via a cable. It ran on six AA batteries, was packaged with a roll of 38mm wide thermal paper that was adhesive on one side, and was in production between the years of 1998 and 2003 after which Nintendo discontinued production. Today the primary way to purchase one is via eBay or other third-party websites and most prices run between $50 to $100

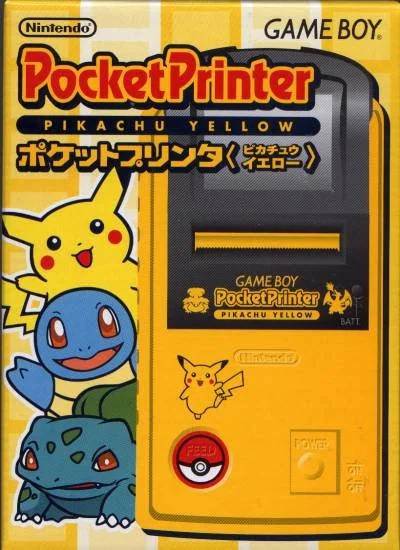

I also note that for Pokemon: Yellow Version there was a standalone Gameboy Printer who’s body was solid yellow, there was a Pikachu on the front of it, and the “print” button was a Pokeball. There was no technical difference between this model and the other Gameboy Printers on the market, but I mean, come on dude that’s just sweet.

I would have bought one.

Photo sourced from Bulbapedia.

There were a number of games released that offered players the chance to print images on the Gameboy Printer, and as I noted one side of the thermal paper was adhesive, meaning that one of the appeals of this machine was that it allowed players to make stickers of scenes from games they were playing. The printer was associated with another hardware attachment known as the Gameboy Camera. This was a small digital camera that fit into the slot compartment of the Gameboy and included a camera lens with a 180°-swivel front-facing camera. I recognise writing this essay in the year of our Lord Neptune 2024, and then most likely publishing it sometime in 2025, the idea of a mobile camera is hardly a revolutionary concept. But this was the late 90s dang it. My Mom was still using film-based cameras, and my family didn’t own a digital camera until sometime past 2006. What’s important is that this machine connected to the Gameboy Printer and thus allowed someone with access to all three components the chance to take and print their own pictures.

So the question becomes, why is this important for Legend of Zelda: Link’s Awakening?

I’ll note that the camera isn’t relevant (it’s just interesting to a nerd like me). But the Gameboy Printer is important because it shows how hardware development influenced the design and narrative structure of Link’s Awakening.

As of this writing I’ve been playing Final Fantasy VII: Rebirth and Legend of Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom. Both of these games are grand, fantasy epics and both of them incorporate a photo mode where players can snap shots of the world around them while also including side-quests centered around snapping photographs. Thinking of other games I’ve played or am playing sporadically I think of Cyberpunk 2077, Red Dead Redemption 2, Animal Crossing: New Horizons, Elden Ring, and Resident Evil 4: Remake. These games include the option of a “Photo Mode” where players can pause the game and make snap-shots of in-game action. And looking at the hardware of contemporary videogame consoles, there is a screenshot button attached to controllers. Whether it’s the Nintendo Switch, The Xbox One, or the Playstation 5 each of these systems incorporate screenshot options because there is an expectation from players that they will be able to take pictures of the game while they play, either for the purposes of sharing images on social media, blog posts, sharing with friends, streaming, or even just for their own personal amusement.

What this means for videogame design is that taking photographs is no longer a novelty attachment, it’s a player expectation.

When Link’s Awakening was remade for the Nintendo Switch in 2019 I played it to completion, and I noted that Mouse’s photo house had been replaced with a mini-game involving the gravedigger Dampe. By 2019 Nintendo had a handheld console that could take hundreds, thousands, millions of screenshots of moments in games, and players could upload those images to the internet with little to no difficulty, and no hardware attachment necessary.

This made sense to me in 2019, and it still does, but there was also sadness because despite the technical reasons for Mouse’s absence, the narrative felt smaller.

Interactions with Mouse in Link’s Awakening were about capturing moments that could be printed out, but they also served the narrative purpose of demonstrating Link’s time on Koholint Island and exploring its emotional weight. The end-goal of the narrative is about Link escaping Kohilint island, but along the way he encounters people with their own unique foibles and personality, Marin being one of the best examples. She tells him, in a beautiful cut-scene that I desperately want to write about someday, about her envy of seagulls and how she wishes she could fly. She even tells Link that she dreams about becoming a Seagull and flying away and off the island to see what life is like beyond the seemingly endless expanse of the ocean. It’s a beautiful moment that I still think about decades after playing the game for the first time. Returning to Mouse’s hut later will reveal that, during this exchange, he was present and managed to capture a snapshot of Marin and Link gazing at the ocean and sharing this moment together.

It’s worth emphasizing, this moment was saved for posterity for narrative purposes, AND to promote the use of what my girlfriend effectively called “A sticker maker.”

Mouse exists in Legend of Zelda: Link’s Awakening primarily because Nintendo was trying to promote and sell a product. From that aspect alone he’s interesting for ludology (fancy-pants word for study of games and gaming).The intersection of commerce and art, and the pull between them, is a constant in videogame studies and analysis, and for a nerd like me it provides endless hours of entertaining research and consideration. Software development is always reliant on hardware limitations as well as possibilities, which is to say as long as a machine can be built that can facilitate a creative vision anything is possible. Every generation of videogame consoles has arrived with a small handful of truly great software programs (along with a mountain’s worth of okay ones (and then far too many subpar ones(and only ever one that’s so truly terrible that it’s good))), and while these programs exist there has been untold numbers of promotional services, activities, and products to enhance players’ experience with the game and also to create extra capital for the companies that have developed this software.

Looking at a machine like the Gameboy Printer is fascinating because it a demonstration of how the videogame industry tends to operate as a kind of ourobouros (the snake eating it’s own tail).

Software was designed to sell and promote hardware, and hardware was designed to promote and sell software.

What becomes incredibly fascinating is what happens when the hardware that’s designed to sell that original software changes or becomes entirely irrelevant.

Hence, I return to Mouse.

Decades later Mouse still exists in the original software, but the hardware he served to promote has been completely abandoned by the parent company, a.k.a. Nintendo, making his “purpose” in the game irrelevant. At the same time this has honestly liberated the cold utilitarian function of his existence and unintentionally heightened how well he worked for the narrative.

Mouse shows that Link’s time on the island was not always adventure and combat, but composed of a series of small social interactions that had a real depth of humanity. The people of Koholint were quirky, bizarre, funny, and beautiful. And so was Mouse. He made me want to explore every corner of the island just to see if there was a snapshot somewhere that could be taken, and just about every interaction offset the dramatic tension and existential crisis that the main narrative was building. This is to say, I didn’t stop worrying whether or not the island, and everyone and everything in it was a dream, but watching him fall off the side of a mountain to snap a photo was a great laugh. In this sense he was somewhat a comedic relief, but he was also just another one of the strange souls of this dreamy island of mystery.

Somehow Nintendo managed to create an npc that existed originally to just sell a small thermal printer, and then managed to have a soul.

Joshua “Jammer” Smith

11.24.2025

Like what you’re reading? Buy me a coffee & support my Patreon. Please and thank you.