Pokemon Snap: A Photography Rail Shooter…with Pokemon!

While the boys my age were killing each other in Goldeneye 007, I was snapping pictures of Electobuzz and Rapidash and enjoying my life immensely. I also note for the record that they would soon be moving on to Gears or War and Diablo II while I was still snapping photographs of Electrode and Magnemite. My family wasn’t rich so I was typically one console generation behind everyone else. Not that it actually mattered. I was obsessed with Pokemon, like every Millenial was at the time, and Pokemon Snap afforded me an experience where I was able to interact with these animals/monsters in a way that wasn’t centered around competition and violence. Except for when I threw smoke-balls or apples at them but I’ll get to that in a bit.

Pokemon Snap offered me, first and foremost, the experience of immersion into a natural environment where Pokemon were just existing without concern about whether or not I would be capturing them for my own personal goals.

Despite the fact that most of my current videogame time is spent on action-adventure games and first/third person shooters, looking backwards I recognise there were a number of games that I spent my time on that were just about…well, vibes. There’s almost certainly a better word than vibes in the English language to describe the experience of just playing interactive media for the sake of just enjoying simulated atmospheres, but nothing comes to mind.

Maybe Gallipoli?

But I’m pretty sure that’s some kind of coffee.

Wait, nevermind, I googled it and it’s a peninsula in Eastern Europe. It still feels right though for describing the experience of watching Snorlax dance by a beach or Pikachu pretending to surf.

Gallipoli.

Ga-Lip-O-Lee.

Anyway, back to videogames.

Game cover image provided by Moby Games.

Pokemon Snap was released for the Nintendo 64 (N64) console system 21 March 1999 and completely rocked my world. Released literally a month before Pokemon Stadium, I was seeing Pokemon on a television screen instead of an eye-strain-inducing Gameboy color screen, and in beautiful blocky 3D to boot. Also, unlike every other Pokemon game released on the market, I wasn’t trying to catch these Pokemon for fights, I was just trying to catch their likeness…on film.

That was a horrible sentence and I apologize for it.

Pokemon Snap is, structurally speaking, a Photography simulator, as well as a first-person, Rail-shooter game, a sub-genre of the Shoot ‘em Up genre. Rail Shooters were popular and prevalent on the Nintendo 64 (Star Fox 64 being the most popular example) because they allowed developers to play with the 3D graphics, while also not having to develop full 3D environments. Rail-shooters are, by design, tracks where players will typically control an avatar in a fixed space (either contained on a line or within the square of the monitor), and as the world approaches the player’s avatar various non-playable characters(npcs) will appear. Typically Rail-shooters have been about controlling jets, airplanes, tanks, or some variation of science-fiction vehicle and as such many npcs in these games have been enemy jets, tanks, robots, giant robots, insects, or giant insects. Players are given a target point on the screen they can control and, using the various action buttons they have access to, will fire munitions to destroy these enemies. The goal becomes moving the target point to the enemy in time to accurately fire one’s weapon and hit them.

I have to be honest here, I’ve never been good at rail-shooter videogames, so I haven’t spent much time on them. I’ve enjoyed playing them when I have, but for the most part they require reflexes that I have not, and just will not ever possess. And this is a tragedy because Rail-shooters can be really fun.

Just like Pokemon Snap.

That was a terrible transition, and management just informed me I’m allotted only three more mistakes before they replace me with a writer half my age and a better credit score.

You buy one true-to-size 3D Printed Bile Titan from Helldivers 2 and suddenly you’re labeled an economic pariah and no longer invited to Timothy’s bar mitzvah.

Anyway.

Pokemon Snap is fascinating to me because it took the structure of a rail shooter and replaced the gun with a camera. Now as of this writing there’s an entire discourse in videogame analysis about the prevalence of firearms as the primary system for interacting with in-game worlds. For the purpose of this essay, I won’t be discussing that topic in depth, but I did want to acknowledge it as I focus on photography as a unique design-element because, honestly, I haven’t played another photography simulator since Pokemon Snap. Most of the games I play and have played involve weaponry as the primary system. Whether it be Borderlands, DOOM, Helldivers 2, Fallout 4, Cyberpunk 2077, Red Dead Redemption (1 & 2), or any of the Resident Evil games, guns have been the main interface. While considering this list I honestly wonder how these games could be redesigned to incorporate non-violence as a system for players. Most contemporary Triple-A videogames are packaged with a “photo-mode” where players can take screenshots to share on social media, and some games even incorporate photography as side quests. Heck Red Dead Redemption 2’s side quest about famous gunslingers involves Arthur Morgan snapping photographs…and then usually killing aforementioned gunslingers. Players are becoming more accustomed to capturing still images from simulated realities, and so it makes logical sense that, at some point, a photography-centered videogame could and should become more than just a side-quest.

Let me clarify, I’m not arguing for removing firearms from videogames, because I love shooters. Rather, I’m trying to observe how photography as a system has been absent from most of the interactive media I’ve played.

Before I get too lost in this thought though, let me return to Pokemon Snap and get the narrative established.

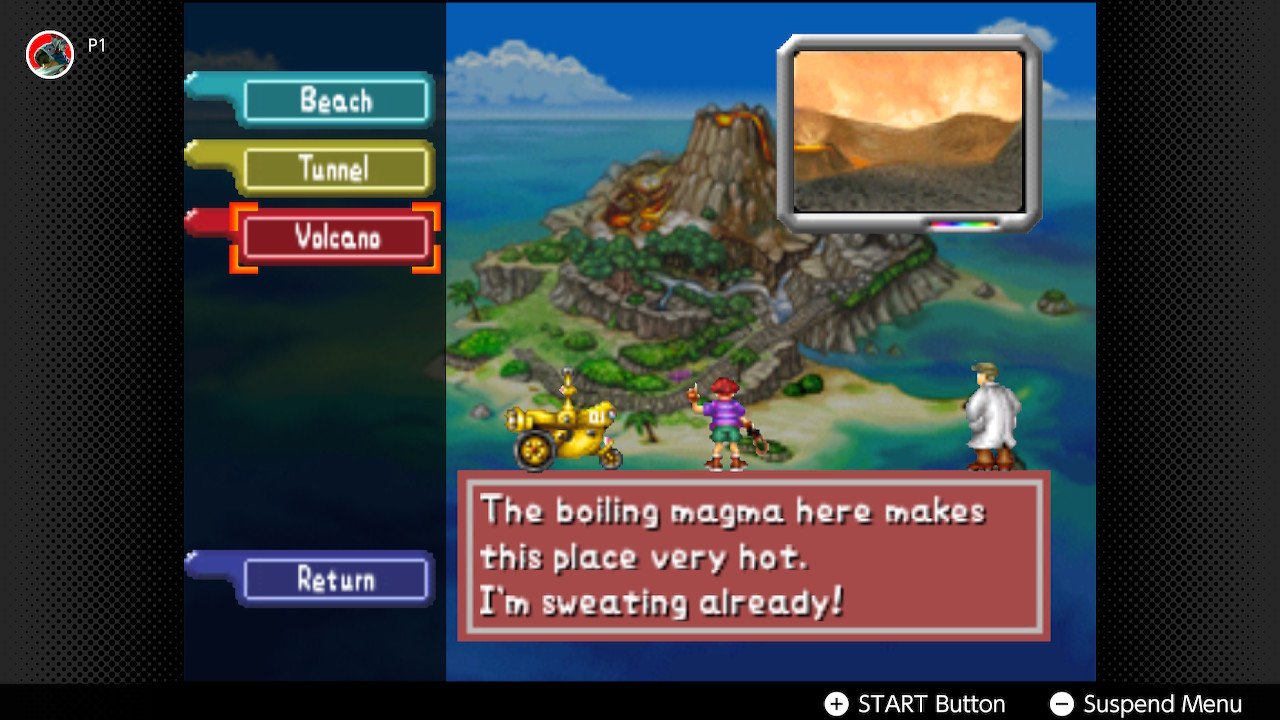

The narrative of Pokemon Snap is a photographer literally named Todd Snap (I’m not even kidding) has been hired by Professor Oak to come to Pokemon Island and take photos of Pokemon. Professor Oak being the O.G. Pokemon Professor (who’s almost certainly acquired tenure at this point) wants images of these animals to accompany articles and books he is going to publish, and he knows that Todd Snapp is the perfect person for the job. Professor Oak provides Snapp with a film-camera (don’t forget yall this is 1999 (cameras ain’t digital yet(least to poor folks like me))) and an amphibious buggy called the “Zero-One.” The game is broken up into levels starting with a beach and ending on the periphery of the planet's atmosphere. Each of these levels has unique aesthetic design, specifically in terms of its environmental quality. The first level is a beach, followed by an abandoned power plant, there’s a river filled with vegetation, there’s an active volcano, and there’s a cave brimming with Zubats. The Zero-One will move along a fixed path and as Pokemon approach the vehicle Snapp can snap photos (omg I just got that) which is exactly where the Rail-shooter design comes into play.

Player’s can’t leave the Zero-One to adjust the angle of the photos they take, nor can they stop the vehicle, they can only slow it down. The perspective of the game is first person with a wide-angle to observe the world around me, or a zoomed perspective which is triggered when I’m ready to snap a photograph.What this means for gameplay is that I’m restricted to a set path, and my ability to capture images of these Pokemon is determined on my ability to react in time, and center my lens cursor at the right place at the right time.

Fun fact, I suck at this.

It's frankly shocking that I was ever able to even snap a photo of a flipping Pidgey let alone a Zapdos.

Like I said originally, I enjoy rail-shooter videogames, I’m just not good at them. The reflexes necessary to anticipate enemy movements, and center the cursor on the exact spot at the exact time is a challenge, and one that I failed more often than succeeded at. However Pokemon Snap differed from traditional rail-shooters because missing a perfect shot did not result in my vehicle acquiring damage. It just meant that I would have to do the mission again and hope I got the shot on my second run...or third run…or eleventh.

One easy example takes place in the first level. As The Zero-One moves along the track, Todd will observe several Pokemon just existing, and there are several instances where taking one photo will result in missing another one. Near the start of the levels there will be a Lapras emerging from the open ocean. Likewise there will be other pokemon nearby such as Pidgeys, a Pikachu, and even a Doduo who’s running about and honking to its earthly delight. My choice at this moment is to grab the shot of Lapras or try for any of the other Pokemon on the beach. It’s seemingly not a difficult choice since Lapras is far out and hardly visible. I usually would take the shot of Pikachu because…I mean, come on dude it’s Pikechu. I mean, I’m not not going to take cute photos of Pikachu. This choice, like any well-crafted game, prioritizes choice and demonstrates that there are results of choice because as Todd continues through the course there will be more appearances of Lapras emerging from the water until, near the final section of the level there will be a small lagoon, and if I’ve taken pictures of every appearance of Lapras there will be three of them now, and one of them will be close enough I could practically reach out and touch it.

Pokemon Snap was filled with these small Quick-time events that triggered immediate and consequential reactions. These could range from getting Pikachu to pretend to surf on a board to triggering a group of Magnamites to evolve together into Magneton. Pokemon would literally respond to being photographed. Admittedly this is at its core just the coding structure of the game itself. However, it was 1999 and I was a kid who was watching Pokemon react to my actions. The aesthetic effect was palpable and immediate.

This is to say, I loved this, I was obsessed with this, and I loved life while I was playing it.

I mean, I could make Snorlax wake up from his slumber and start dancing. And not just a little wobble either, the dude would be shaking back and forth and straight rocking to the beat of my Poke-flute. Literally the best Pokemon was dancing because of a choice I made and I got to snap a photo of it.

I always want to be transparent in these essays about my motivations and I freely admit I wanted to write something about Pokemon Snap partly out of nostalgia. When I consider my “Nintendo 64 era” the games that I recall vividly were Kirby 64: the Krystal Shards, Super Smash Bros, Ogre Battle 64, and Pokemon Snap. These were the games I spent a majority of my time with and so naturally there’s a lot of emotional energy wrapped up in the memory of these games. I like and want to remember these days playing this game fondly, but nostalgia is a thin flume that can disappear just as quickly as it arrived, and its psychological odor, though pleasing in memory, can age like vinegar when reality sets in.

That’s a fancy-pants way of observing that sometimes videogames I appreciated in my childhood didn’t age well, and I’ve realized I only liked it because I was a kid.

Playing Pokemon Snap on my Nintendo Switch I recognised immediately that this game was not great, mostly because of the motion controls. My camera is slow, and by the time I’ve framed my shot a Pokemon has moved out of the shot forcing me to adjust quickly to the next possible shot which I typically stumble through. Part of this is simply because of the hardware of the original game and the (unique?) structure of the N64 Controller. Gameplay-wise the Pokemon are still cute, but their motion is often stiff, and because they will always be in the exact same spot the sensation of playing the levels multiple times is like being on carnival ride and observing animatronics rather than flesh and blood organisms. And this last point is important because players will have to loop through the [SEVEN] levels of this game multiple times as they unlock more items and inevitably miss shots.

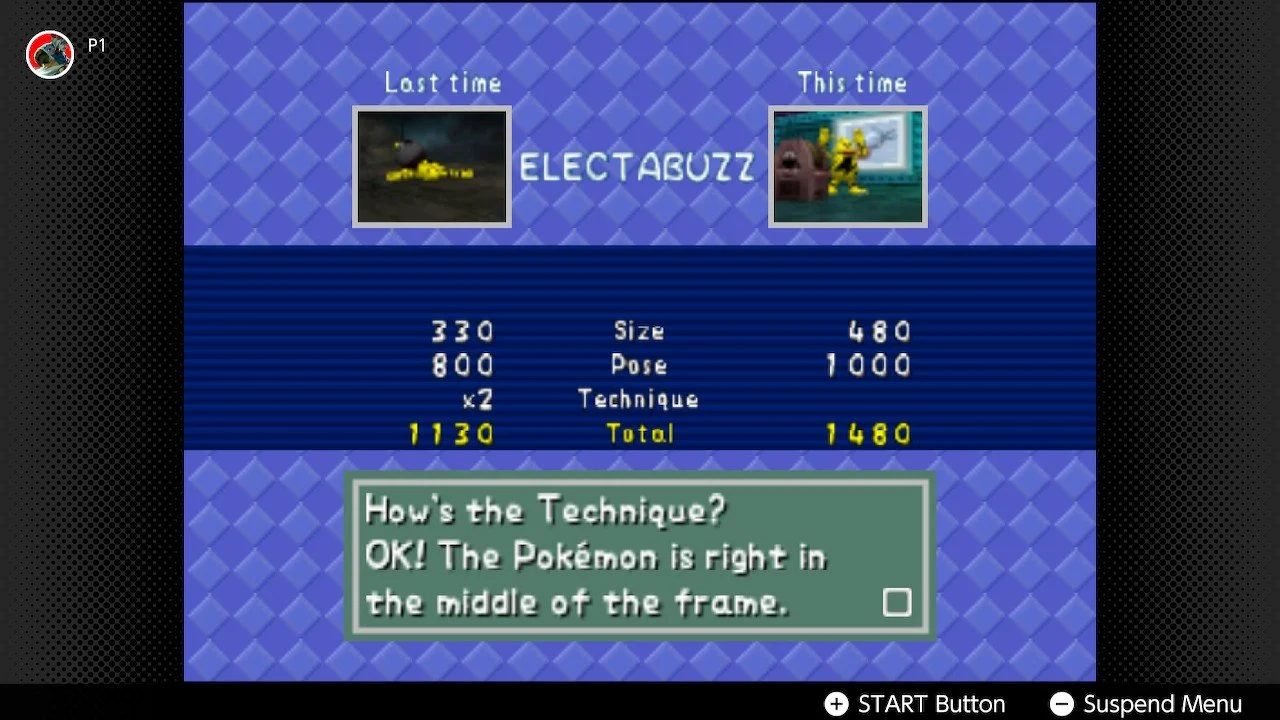

Probably the most frustrating aspect of play however is the photography rating that takes place after each level. Once I’ve finished a run I will have to select the best photographs I took to submit to Professor Oak and I say this as professionally as I can, the dude is about as forgiving as Gordon Ramsey. Professor Oak will comment on the structure of the image, the placement of the Pokemon, the pose it assumes, and assign score values.

Spoiler alert, just about all of my photographs suck and Professor Oak will tell me to “try better next time.”

Emotionally these critique sections are painful to endure, even as I recognise myself improving because there is always the knowledge that I could have almost certainly taken a better shot. Just like a run of StarFox 64, the conclusion of every level is a collection of points and it doesn’t matter how well I did, I always come away with the nagging perception that I missed something, or that one sequence was handled poorly and thus resulted in the entire level being a failure.

But, structurally speaking, this is where Pokemon Snap demonstrates the brilliance of its design.

Photography is an art because it requires practice, diligence, patience, and repetition in order to improve. Just like drawing, writing, painting, learning a musical instrument, dancing, etc., Photography requires me to just try over and over again while also studying my failures (not for the purpose of shaming myself(though that doesn’t stop me)) but rather to understand what it was in that moment that caused that mistake. Most of the time it’s usually just an issue of reflexes, I took a shot too early, I took a shot too late, I positioned my cursor too much to the left or right where I originally anticipated the path of my subject to be etc. And these errors are exactly the same for any rail-shooter videogame. As insects, tanks, planes, and robots move across the screen I attempt to make sure that my cursor is centered on my enemy, or else try to anticipate where they will be before pressing the action button and thus launching whatever ordinance I have at my disposal. The core experience is a point-and-click interface built around learning a system and the physics that guide it.

Pokemon Snap then isn’t a true photography simulator, but it’s also never trying to be one. It’s only ever trying to be a fun videogame about taking cute pictures of Pokemon.

Pokemon Snap was about being immersed in the world of Pokemon, and while the repetition of levels doesn’t offer players much in the realm of replay value, the game is still interesting from a Ludic perspective because of its structural design, and for the way it offered a pseudo-photography-simulation experience.

The game was a fun vibe, and I played it as much as I did because I loved the world of Pokemon and enjoyed the concept of just observing these animals/creatures in a pseudo-natural environment. I enjoyed the battle mechanics of the other games, don't get me wrong, but I always wanted to see Pokemon outside of one-on-one battles. There was a world in the tall grass where Rattas, Pikachus, Voltorbs, Hypnos, Mr. Mimes, and Cubones were just living like wild animals, and I wanted to see it, exist in it, and maybe try to snap some photos.

Pokemon Snap gave me that world. It gave me the space to just watch and be amongst Pokemon.

And, it’s worth repeating, the game let me make a Snorlax dance. How can you beat that dude?

Joshua “Jammer” Smith

12.15.2025

Like what you’re reading? Buy me a coffee & support my Patreon. Please and thank you.