Super Mario Bros. 3: What’s In (or on) a Map?

I want to write about the importance of innovative visual aesthetics in graphic interface design, or, excuse me, what I meant to say was, I want to write about Super Mario Bros. 3.

Wait.

Actually, that’s the same thing.

Super Mario Bros. 3 was released 23 October 1988 in North America for the Nintendo Entertainment System(NES), though I note that when I played the game it was on my parent's Super Nintendo Entertainment System (SNES) on their Super Mario All Stars Cartridge. I spent a lot of time with that cartridge, so much so that when I played the original NES version on my Nintendo Switch sometime in my early 30s there was a profound culture shock. I also note that, Super Mario Bros. 3 has been released for the original Famicom Console, an arcade version in 1989, the Nintendo Gameboy Advance in 2003 (it was packaged under the game Super Mario Advance 4),the Nintendo Wii in 2007, the Nintendo 3DS in 2013, the Nintendo Wii U in 2013, and then finally was released for the Nintendo Switch in the NES Emulator application in the year 2020. This list alone serves as a fascinating, and rather convincing argument for the games lasting appeal to players, not to mention Nintendo’s incredible ability to make players like me pay for the same damn game over and over again.

As the Roman poet Publius Virgilius Maro, a.k.a. Virgil the writer of The Aeneid so expertly noted, “Hate the game, not the Player.”

Virgil’s reflections on the Kid Icarus series are also worth exploring if the reader has time. Bit long at 1000 pages, but still a far more enjoyable read than The Aeneid.

Just saying.

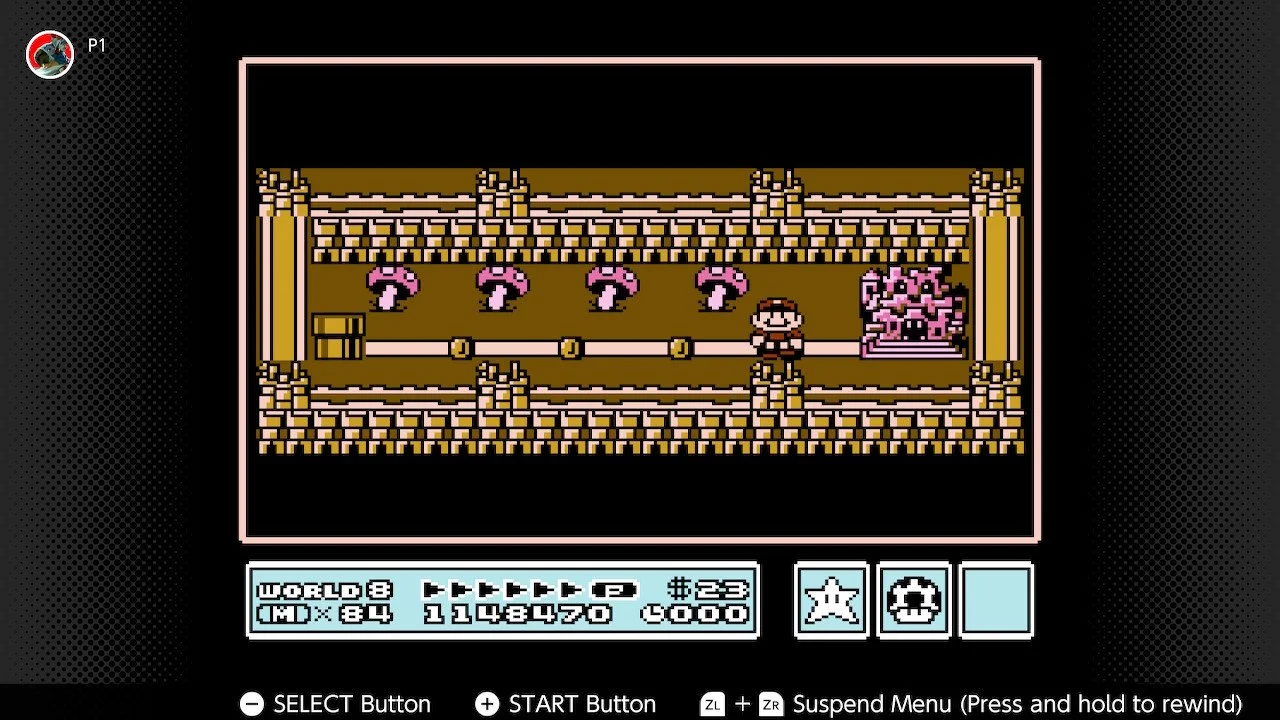

In terms of gameplay Super Mario Bros. 3 is a fantasy, action, platformer game with 2D scrolling, side-view perspective. Mario travels through various kingdoms in order to save the kings of each land who’ve been transformed into animals by Bowser’s children the Koopalings: Larry, Morton, Wendy, Iggy, Roy, Lemmy, and Ludwig Von Koopa. By the time Mario defeats the last Koopaling he discovers that Princess Peach has been (spoiler alert) kidnapped by Bowser and is being held captive in his castle. Mario will eventually defeat Bowser, rescue the Princess, and everyone lives happily ever after...at least until the next game.

Super Mario Bros. 3 is an incredible videogame in terms of it’s playability, it’s replayability, it’s visual design, it’s control mechanics, it’s minigames, and for its role in developing and establishing the Super Mario franchise as a legacy title for Nintendo and thus setting the stage for later games such as Super Mario World, Super Mario 64, and Super Mario Sunshine. I’ve already written one essay about super Mario Bros. 3 for this website, but the depth of its design is such that I know I’m going to write more in the future.

And at least one in the present.Speaking of which.

I’ve been thinking lately about my original review for Alysse Knorr’s book Super Mario Bros. 3, one of the books in the Boss Fight Books series which I’m a fan of. I loved Knorr’s book and have found myself returning to it regularly for ideas. Skimming through it I found a few paragraphs about the map and how it’s design was not only distinct from previous games it was also an innovative graphical interface for players. About the same time I was re-reading the book for quotes I decided to rewatch Norman Caruso, a.k.a. The Videogame Historians video about Super Mario Bros. 3 and in the video he observes how the game differed so greatly from its predecessors in large part because of the interactive map players used to select levels.

Obviously, at this moment I had the topic for another essay.

And you’re reading it.

And you’re probably also not drinking enough water.

I recognise a map may not seem terribly revolutionary, but it’s important to consider the context of the game against its predecessors. The first Super Mario Bros was designed so that, when players entered the brick castle at the end of each level the screen would fade to black, the title of the next level would appear, and the screen would open to the new level. There was no player action involved in this process; the game shifted from level to level without player input. This system continued in Super Mario Bros. 2 where players would complete a level and then immediately be taken to the next stage. This transition system makes sense on a technical level since, at that time videogames, but more specifically the hardware used to manufacture and play videogames, was incredibly limited. To put it in perspective, the original Super Mario Bros was a total of 32 kilobytes while one of the most recent game in the series, Super Mario Odyssey, is 5.7 gigabytes (that’s about 5 million kilobytes). By the end of the NES’s tenure designers had access to more powerful equipment, and they had explored the system to determine how to push its hardware to afford as much play and visual design as they could.

And boy howdy, did they deliver.

Alysse Knorr provides a wonderful description of the first world map, and manages to brilliantly capture the energy of this new design. She writes:

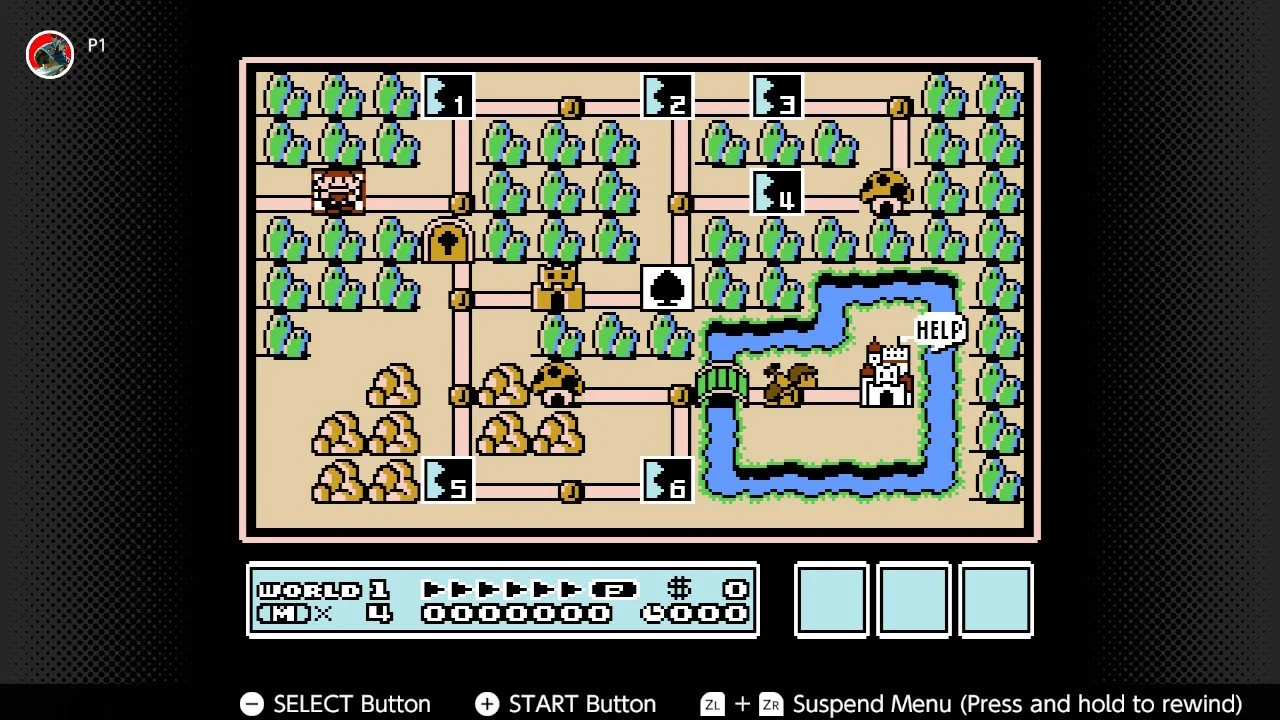

Ninety-four bushes dance in time to the music on the screen.They're adorable little bushes despite–or perhaps because of–the fact their sole facial features is a pair of large eyes. They bob up and down in pairs of big and small, as though 47 mother and baby bushes all went out to enjoy a beautiful day in Grass Land. Except for the word “HELP” flashing over the White Castle and the armed patrolmen pacing obsessively at the castle moat bridge, all seems well here.

SMB3's first world map is a friendly introduction to the Mushroom World. The entire map is contained on one screen, making it easy to see your goal in the bottom right corner. The Mario sprite moves his little feet and hands back and forth quickly–faster than the music, the trees, and the pacing hammer Brother. Bowser has struck again–this time with the help of his Koopaling children–and someone has to stop him. Mario is ready to get down to business. Are you? (4).

I can’t honestly remember the first time I played Super Mario Bros. 3, that’s more a statement on how long I’ve been playing Super Mario videogames than anything else, but I do recall spending hours playing it and just moving Mario around the map. Each world I explored was a visual spectacle and there was a wonderful sense of progression as I completed each level and watched the solid black squares fill up with gargantuan, red “M’s”(and occasionally “L’s” if I was playing two player (by myself of course(I didn’t have friends))). The freedom of movement was my first impression since now I wasn’t just occupying space within timed levels, in fact there was no time limit on the map. I could just be here, in this world, moving along the paths without concern that some omnipotent clock would soon begin ticking down reminding me that I was almost out of time. That freedom of movement, and freedom from time limits, was everything in really creating the impression that Mario was exploring a real simulated world.

And on the note of exploration, Knorr demonstrates how much the path inspires that desire for exploration in the next paragraph. She writes:

A closer look at the map screen reveals a first glimpse of what's different about SMB3. The coins on the paths between the levels are a familiar sight, but what are those mushroom icons? We know from Super Mario Bros and Super Mario Bros 2 that mushrooms are a good thing, so the sight of these large mushroom houses is immediately tantalizing. Are those two castles?An entirely separate fortress(more visually reminiscent of the castles in SMB1) plopped square in the middle of the map blocks your way to the white “HELP” castle at the end. And there are more than three levels on the way to that fortress! What is this crazy game? And what happened to Mario's standard “three-levels–then-a-castle structure? (4-5).

Before I build off of this quote I just wanted to call attention to Knorr’s use of questions and how much I love it. I personally adore using questions in nonfiction writing because it always feels personable, and it also, in my opinion, reminds the reader that writers are just people trying to make stuff. I never want to portray myself as anything other than just some dude with access to a word processor and that’s one of the reasons why I use so many questions. Knorr manages to regularly employ questions here to invite the reader into her curiosity, while also managing to accurately convey how this new map will likely impact players who only ever played the first two Super Mario videogames. Knorr is, above all things else, a gifted writer and she always manages to convey her wisdom and experience while also demonstrating the work that went into this wonderful book.

I’ll stop sucking up now I promise.

My nausea-inducing apple-polishing aside, the preceding passage is important because it demonstrates that the map of Super Mario Bros. 3 wasn’t just an innovative design because it afforded players the option to move around a screen between levels. A map is a useful structure for creating a larger narrative within a videogame, but at its core the interactive aspect of exploration sets the foundation for a sense of curiosity and further engagement. It wasn’t enough that the map had levels in it, it also had mushroom houses where players could acquire power-ups like the tanuki suit, it had pseudo-slot-machines where players could win extra lives, enemy npcs would move around the map after players finished levels giving a dynamic energy to actually playing the game, and the castles at the end of each level provided players with an end-goal.

This map gave players choices to make between levels.

And Alexander the Great observed after conquering Persia, “Choices = good.”

It’s important to remember that Alexander the Great claimed to be a total gamer, but as far as the historical record is concerned that dude only ever played Duck Hunt once, on his friend’s Dad’s NES one time, and he killed like one duck and then immediately started bragging about how he “solved” the Gordian Knot.

The point is, Alexander the Great sucks, and, the map in Super Mario Bros was a wonderful design because it gave players more options for play.

Moving Mario across this map was pleasant, heck it was downright fun, but the actual joy of moving Mario was about moving him forward through this world (and every world Mario will encounter). In fact as Mario and players progress through the game the maps become far more complicated, and just finding the right progression becomes a great joy of the experience.

Knorr says as much in a later passage of her book when she writes:

The map screen–the tool that helped users explore SMB3's world–was just as revolutionary as the themed worlds–not in terms of technology, but in how cohesively it was integrated into the game. “An overworld map was nothing new, but SMB 3 did something different,” software development engineer James Clarendon said. “Early titles such as Sega’s Kenseiden also had an overworld with a geography and a raison d'etre (Feudal Japan), but there was little to separate it from being a glorified level select menu. SMB3 makes the overworld part of the game. It gives a true sense of progression through themed worlds where there is a clear and established flow: You can see the roads that connect the levels, you can mentally build a path to the goal and the branches enable players to skip(or expend resources to avoid) difficult levels.”

Even better, SMB3’s map screens meant that gameplay was no longer limited to levels themselves any more. On the map screen, players could chase the Koopaling airship around, paddle in a canoe, use special map screen items(like the Anchor Music Box, Hammer or Lakitu’s Cloud), or find unique map screen secrets via pipes and brick breaking. Meanwhile, the Hammer brothers created unpredictable challenges on the map screen and offered players one more type of mini game and reward. I'm not sure if the Hammer Brothers were supposed to be guards, mercenaries, trolls, or just traveling jerks, but they are the perfect set of “brothers” to rival our heroes. (111-112)

The world maps of Super Mario Bros. 3 are not static images that facilitate breaks between levels, they’re as much a part of the play as the levels themselves. As Knorr demonstrated before, the player is given options besides just moving from one level to the other, and as the player progresses they will discover secrets that provide them options on how to ultimately reach the end goal. Likewise the minigames players will find will provide players with new items. The Hammer Brothers that skulk about the map for example are a quick fighting minigame that will reward me with power-ups like hammers for breaking stone walls, tanuki suits which will make navigating levels easier, and sometimes it’s just Super Mushroom which will make Mario grow.These fights were enjoyable in and of themselves, and when I was younger I would create narratives about these npcs while I was playing. Sometimes I would purposefully play levels out of order to see if the Hammer Brothers would walk out of my path thus allowing me to simply move past them.

In hindsight, this interactive map gave me access to early experiments with software interfaces.

Though nowhere near as engaging as Super Mario Bros. 3 I would later be taught in school, and my parents, how to work computers and use productivity software either for school or for managing personal finances. Obviously I never used a Tanuki Suit while working with Microsoft Word (though not for lack of trying(and who’s know maybe that will be option whenever they publish the Windows 12 operating system)), but I had had enough experience with learning the interface structure of the map so that I could easily determine what the menu options were, how to move my mouse across a screen the way I would Mario, and determine which buttons and menus would respond to button presses. Just playing the interactive map of Super Mario Bros. 3 taught me the lesson that computer software, regardless of whether it’s purpose is professional or for play, is composed of the same general structure of input and output controls.

It’s easy to forget that consoles are actually just computers with specific functions. The earliest consoles were about running entertainment software exclusively, but videogame designers were as much engineers as they were game-makers and so as they made games and stories that defined a generation, they also (intentionally or otherwise) helped bridge the gap between personal computer interfaces and entertainment products.

I believe an argument could be made that the maps of Super Mario Bros.3 were almost edutainment in terms of their structure and interface. Just like Solitaire taught generations how to use a computer mouse, Super Mario Bros.3 taught kids like me how to navigate computer menus.

Before I disappear down that train of thought however, it’s important to remember people played Super Mario Bros. 3 because it was a fun, platformer videogame. It was fun hopping on Koopa-Troopas, discovering secrets in the clouds, defeating Iggy Koopa, dodging bullets on flying ships, timing jumps just right to knock the literal sun out of the sky, or sometimes just figuring out how to progress easily through the game.

Which on that note, I should talk about the Warp Whistle.

In the original Super Mario Bros. there were hidden chambers where there were typically one to three pipes that would allow a player to skip through worlds. For example in World 1-2 of Super Mario Bros a player could skip to levels two, three, or four. Instead of pushing through the three levels and then defeating Bowser, this would let me just get to the end of the game faster. Part of this design was most likely to allow arcade players to reach later levels and give them a sense of accomplishment (and maybe also spare their pocketbooks a little bit since quarters cost money(actually they ARE money)). Super Mario Bros. 3 didn’t have this structure, but it still offered players a similar choice. If players were able to get a Warp whistle in Toad’s chest-opening mini game they could skip an entire level.

Alysse Knorr offers a more detailed explanation, and technical insight when she writes:

Furthermore, while the warp features of SMB1, SMB2 USA and SMB2 Japan had been embedded within levels, SMB3’s take place on the map via the Warp Whistle. Miyamoto first used the Warp zone concept in the arcade version of Excitebike, in which players could choose which of three levels to start.So they could skip levels they'd already mastered.

SMB3’s whistle makes the warp feel much more climactic than SMB1’s room of three pipes. The whistles eerie melody(which is the same song played by the warp whistle in the Legend of Zelda) and white tornado (also the same one from Legend of Zelda) add a mysterious ambience as you're whisked off the screen to an entirely different map– the island of pipes named “Warp Zone” that may technically count as the ninth world of SMB3. As Bob Chipman points out, the Whistle, which actually resembles (and sounds like) more of a recorder or flute (it's called “recorder” in the Japanese translation at “Magic Flute” in Spanish and German) marks the first time in Nintendo history when game designers self-referentially recycled sounds and sprites from a different Nintendo franchise, perhaps to point out the “gaminess” of the game–one of SMB3's many inside jokes secrets. (112).

I never managed to find a Warp Whistle in any of my playthroughs of Super Mario Bros. 3. While there’s a slight disappointment at not having experienced this for myself, it honestly doesn’t bother me too much because I love the game and enjoy playing its levels…except for any level involving Boss Bass but I’ll write about that particular cretinous butt-hole in another essay sometime in the future.

I believe the feminist and existentialist philosopher Simone de Beauvoir also wrote several essays about Boss Bass, but most of them are just the F-word written in all caps over and over again.

Very insightful actually. I cried.

What’s important is that the Warp Whistle, apart from giving players a way to skip through worlds they had already played before, was also composed of technical elements from others games. Anyone who’s watched enough films has likely had the same experience videogame players have had when they observe a reused sound file. One of the best examples if the infamous Wilhelm scream that’s been used in movies and television since the 1950s when it first appeared. Anyone who’s heard the scream once will likely recognise it because it’s been used in movies such as THEM!, Toy Story STAR WARS, Lord of the Rings, etc. The Wilhelm Screem’s also been employed in videogames such Little Big Planet, The Witcher 3, Grand Theft Auto: Chinatown Wars, and Borderlands 3 to name a few.

Nintendo has regularly reused sounds and audio files, sometimes remixing them for newer titles either as easter eggs or because the sounds have almost become branded content unto themselves. But the Warp Whistle’s original structure is important not just because it repurposed sound files. It demonstrated one more choice players had on this map and how to navigate the world they were playing in.

And, plenty more should be said about the legacy of this interactive map because, while writing this essay, I began observing it in other games.

As of this writing I’m trying to play Cuphead…again. I say again because I’ve started this videogame multiple times, never getting past the second Run-and-Gun mission, and it’s frustrating because I absolutely love the aesthetic and, some might argue, I love the punishment of the game which. Cuphead is, to quote a friend of, mine Rubber-Hose Dark Souls.” But putting the difficulty of the game temporarily aside, Cuphead shows its aesthetic influence not just from the Rubber-hose animation style of the 1920s. Cuphead’s levels are reached as players explore Inkwell island through an interactive map, and I use the word explore purposefully. The island has twists and hidden passages that need to be found before players can progress forward in certain areas, likewise it’s only by defeating certain levels that other pathways appear. There are also npcs scattered around the map that provide hints, general world-building, gifts of coins for purchasing power-ups, or directions on where to go. There’s a general store run by a pig with an eyepatch where players can use coins found during Run-and-Gun missions to purchase upgrades for their health points(hp), weapon points, or general maneuverability. The point is, Cuphead’s interactive Map is a spiritual successor to Super Mario Bros. 3.

Cuphead was released in 2017, 29 years after Super Mario Bros. 3, but it's interactive map is practically screaming its design influence. Inkwell Island is as much Grass World as anything else, and just like that world I want to explore every inch of it.

And on the note of exploration Alysse Knorr manages to convey beautifully that perception of possibility when she writes:

In short, SMB3’s map screen offers the player a way to explore each world's diversity, challenges, rewards, and–perhaps more importantly–its scale and complexity. With a big, colorful map charting your every step, the sense that you're on an epic quest had never been stronger than in SMB (112)

This essay has been, if I’m being completely transparent, a way of accounting for my original review of Alysse Knorr’s book. Though I’m excessively hard on myself (just ask my girlfriend, parents, ex-wife, best friends, pets, coworkers, casual acquaintances, and that one drunk dude who sat next to me on a bench in New Braunfels) I recognize when I have not taken extra effort when I should have. Alysse Knorr’s book is responsible for my resurgence of interest in Super Mario Bros. 3, and it’s the reason why I wanted to play it again this time to completion. It’s a wonderful book full of research, personal narratives, analysis, and beautiful passages about her identity as a queer woman.

Reading the passages about Super Mario Bros. 3 and its interactive map made me consider how much time I spent just moving Mario around that map and enjoying making my own stories about his journey. It’s easy for me, as write more and more about videogames to focus on the levels themselves, but I want to also consider how these games are presented and how the navigational interfaces help create the experience. I want to understand how software design plays just as much narrative role as cut-scenes and levels themselves.

Moving Mario around a map is deceptive because at first it’s entirely about entertainment, but upon reflection, navigating this plumber avatar across a map has as much in common with navigating the graphic interfaces of operating systems and productivity software.

There’s an incredible art to this design, and the fact that I can see its influence in games (and other software programs) still being published is proof enough that Super Mario Bros. 3 is an incredible videogame. And it’s proof that a careful artistry went into every facet of it’s design and not simply the fun parts like stomping a goomba or jumping over a Bullet bill.

What’s in or on a map matters as much as making one more jump in a level, because it makes the difference between playing through a world, or truly being in it.

Joshua “Jammer” Smith

10.27.2025

If you’re interested in reading Super Mario Bros. 3 by Alysse Knorr you can pruchase a copy from Boss Fight Books Website by following the link below:

Super Mario Bros. 3 by Alyse Knorr – Boss Fight Books

Like what you’re reading? Buy me a coffee & support my Patreon. Please and thank you.